|

architecture and design

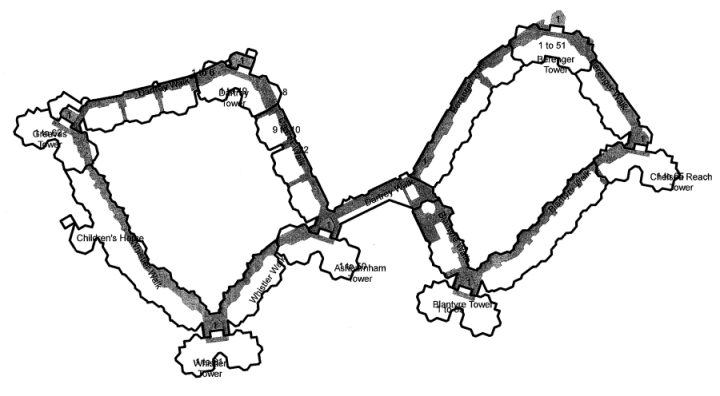

The estate is comprised of 7 high-rise tower blocks of varying heights interlinked by 9 low-rise walkway blocks

in a figure of 8 design with two internal courtyards. All of the buildings abut and merge into each other resulting

in what is effectively a single building.

|

Figure 2: layout of the building showing the seven tower blocks and the interconnecting walkways.

|

The building, as well as the flats within, is of a distinctive many-sided design and the exterior of the building

is decorated by exposed plain red-brown bricks. Both features were intended to help minimize the feelings of "brutal

monotony", "regimentation" and "lack of identity" often cited by the residents of many other large housing estates

of the time. The many-sided "rippled" design helps ensure that residents can see parts of the building at all times

thus helping to engender a feeling of physical security. The same feature also helps relieve the impact of the "crushing

scale" of the building when it is viewed from ground level.

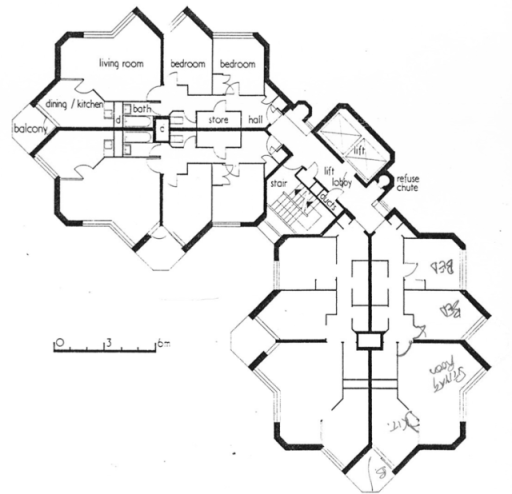

Approximately half of the estate's flats are located within the 7 tower blocks that contain all of the estate's

two-bedroom properties (typically four flats to a floor) as well as three-bedroom duplex units at the very top of

each tower with distinctive turret windows. The other half are located within the interlinking low-rise walkway

blocks, a mixture of bedsits, one-bed, three-bed and four-bed units. The facilities provided within the flats

were a world away from the Victorian terraced houses they had replaced: a permanent hot water supply and central

heating, kitchens designed to accommodate the modern appliances of the time of fridges and washing machines,

large living rooms and ample sized bedrooms. Even by modern standards the flats are large.

|

Figure 3: cross-section of a tower block showing four 2-bed flats per floor.

|

The internal courtyards contain two large garden spaces on the first floor level. These are located directly

above the estate's car parks, which occupy the same space at ground floor level. There is also a significant

amount of green space on the south side of the estate towards the river.

Immediately adjacent to the estate are located a small number of community facilities that were built at the

same time and in the same style. These include the Chelsea Theatre (originally the community centre), Ashburnham

Primary School, St. John's church (which had previously existed on the site) and Omega House (providing space at

ground floor level for that most essential facility, the local supermarket).

The north side of the estate faces towards Kings Road and it is here that a small number of commercial units

are located at ground floor level with frontages onto the World's End Piazza and the Kings Road beyond.

The tower blocks themselves face in a generally southwesterly direction, thus ensuring that the majority of

the residents living within have access to magnificent views of the sunset over west London. It has been argued

that the stunning views provided by the tower blocks, as well as the unique and striking outline they pose against

the London skyline, more than justify their inclusion in the overall design.

|